Dear Friends,

Outside of my field notes, I rarely write in the growing season or near the harvest. Keeping up with the work takes 110% physical and mental presence, but this year I have decided that some things should not be looked at in the rearview. I have wanted to maintain a spirit of both optimism and truth here, and yet I do not want to ever do a disservice to the mission of Hope Well by presenting a prettier version of the truth, or even just the version one sees through the filter of retrospect, with blurred edges.

In previous seasons, my faith in the work and the land have given me the courage to double-down when things start to fall apart. There is a moment in every growing season when I am seized with crippling anxiety and self-doubt, but harvest comes and the joyful memory in my aching muscles takes away the edge. The backwards steps are overcome by more feet forward, and that is enough to light the fire again.

This year. This is a year of the hardest lessons. As we entered a(nother) uncommonly humid growing season it was clear that the reality of ever-more vineyards in our narrow valley means that our fungal foe powdery mildew has more presence than ever before. Organic growers who rely on non-synthetic controls are spraying much more often than anyone feels good about. My concern about mildew outbreaks was dwarfed by my concern over the reality of how much compaction from tractor passes our fragile soils can bear, even with permanent cover crop. We are trying to build organic matter in the soil, an essential component of regeneration, but how can we do that when we have to drive tractors so often to keep our fruit clean?

We managed to reach veraison with clean fruit, but with a heavy heart over what it took to be clean. I was texting constantly with my other organic colleagues: what does this mean? Do we accept this? Can we reasonably argue this is ‘better?’ or just less terrible?

As I tried to console myself that the soil compaction from our organic sprays is less because we have roots in the ground everywhere, and that even if the crop was the smallest on record this year to begin with due to a wet cool bloom period, it was clean and had the promise of excellence, a new plague suddenly appeared: an explosion in the population of voles.

During August our valley looks like the dust bowl. The thousands of acres surrounding us are put under plow, harrow and disc, putting countless tons of topsoil into the air, and leaving thousands of ground-dwelling vertebrates homeless. The vultures and carrion eaters descend to the feast laid in this wake, but the survivors, hungry and thirsty, seek shelter wherever it can be found. Our farm became the refuge just as the driest part of the season came on.

We’ve always had voles, and gophers and moles. These soil vertebrates have a real job to do. They have coevolved with this landscape to deliver mineralized, lower layers of subsoil to mix with topsoil and organic matter and recycling minerals. In the past our snakes and raptors and coyotes have kept their damage to our plants to an acceptable level. This year the predators are so overfed they are killing for sport, leaving the carcasses on end posts and dropping them on the ground. And still, legions skitter about laying waste to the crop. Having built a refuge of permanent cover, in a high cycle year for voles, I now am seeing what I have always feared might be true: our island of diversity and recovery is not big enough to support the failing health of the surrounding ecosystem.

Every year as harvest draws near I walk the vineyard daily doing the late-season perfection pass, tasting the progress. This year every day there is less. Bays full of vines girdled by thirsty voles turn red as the carbohydrates fill up the leaves and the vines produce excess anthocyanins in response. Because of the girdling the products of photosynthesis cannot be translocated to the roots, so those carbohydrates will not be stored for the following year, giving the vine a life-expectancy only as long as it has permanent storage. Bunches of fruit that have been girdled at the rachis (stem) wither and raisin before they have even turned color. Canes that would be next years’ pruning wood are also girdled.

My organic inspector’s advice was to clean cultivate. Break up their tunnels, kill them in the ground with the blades. Obviously, poison is not an option here. Even if I cultivate to try to save what is left, what will I lose in so doing? Ten years of hard work building soil. And if I don’t, why should I believe that next year won’t be worse? And even if we did manage to take the vole population down by taking an action like cultivation, can we afford to replant 30% of this vineyard to repair the damage already done?

If I lose the farm in this lesson because I can’t afford to recover from this, whether I till or don’t till, won’t have mattered much except to me. I, like many others, I’d wager, am forced to choose between what I know is best for the land, and what will allow me to eke out one more little vintage.

I’ve counseled others on transitioning vineyards to no-till. I never lie about what kind of commitment it is, and I never pretend to know all the answers. Being no-till AND organic would challenge the constitution of even the most seasoned veteran. I’ve tried to learn what happens when you keep walking the line, my faith that the system is constantly trying to rebalance itself has been my companion on that lonely road. How will we ever know if this works otherwise?

Failure is not scary to me. We’re good friends. I value the opportunity to learn. And sadly, I feel I have learned the most critical lesson yet: In an ocean of conventional, extractive farming, islands of regenerative practices will meet insurmountable challenges unless the farmer is wealthy enough to continue to throw money into the farm that has no offset in the profits afforded by value-added markets.

But even more to the point, I have always said, and I still believe, that the people who deserve and desperately need the truly nutritious food that can only be grown regeneratively, cannot afford the price of admission. The rich people who can afford to farm this way and eat this way will not find safe-haven when the real reckoning begins.

The mission of Hope Well is to look for a way to change agriculture. In twelve years I have learned so much, and every answer has posed new questions. We cannot allow ourselves be lured into believing that invoking the words ‘regenerative agriculture’ is somehow also an action. At the heart of this concept is old wisdom, a way of living with the land that requires patience, humility, and faith. It is noun and verb. For our land managers to adopt this way of life, society must adopt it with them, in support of them, for a better future for all. It must be adopted on a societal and a landscape level, on a scale that can succeed, that is not just hanging on by threads on tiny islands eroded on all sides by conventional extractive agriculture. Regenerative agriculture must become the conventional way if we are going to find our way to systemic justice, ecological repair, and climate resilience.

I write to think, and to first separate, and then reconcile the emotional experience of doing this work with the scientific observations that doing the work has afforded. As I began writing this, all I could see and feel was the barriers, the damage and destruction. All I could feel was the weight of failure. But I opened one of my million field notebooks and looked back over the year, the sightings of new wildflowers (a few), the return of our wild bees to the hive tree, the (much) bigger populations of predatory arthropods, soil invertebrates, bluebirds, tanagers, horned lark and scores of other creatures and plants.

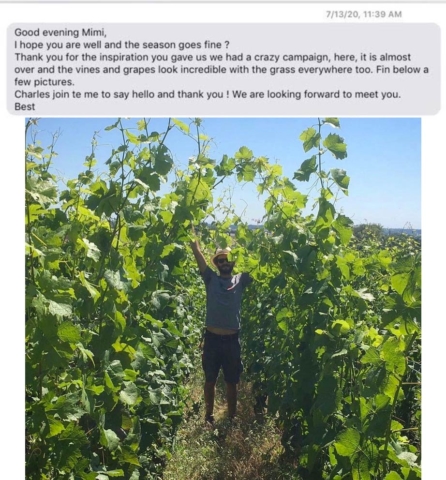

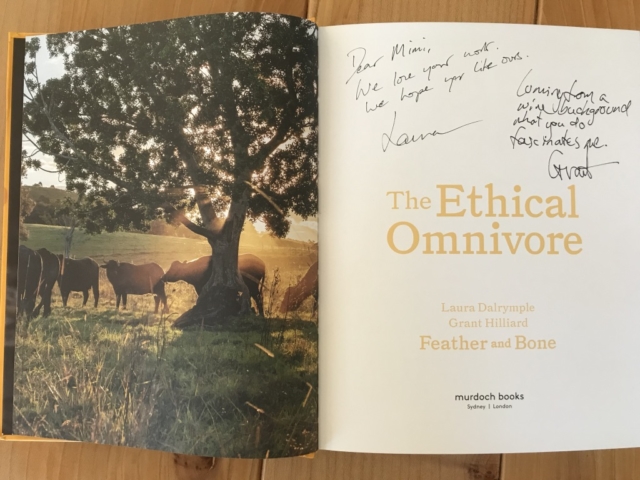

But ABOVE that, in these darkest moments, without ever reaching out, I have been surrounded by the unsolicited love and almost deafening support of old and new friends who are on this journey too. Like a counter-flood to the voles, the love came in connections across oceans and lanes and walks of life: new friends from Provence who are using their considerable marketing prowess to raise awareness of holistic management; a young Burgundian from an historic estate who went full-force into no-till winegrowing where it is virtually unheard of; an American in traditional Burgundy who is transitioning ANOTHER historic domaine to regenerative practices; the most timely and heart-stopping letter and a beautiful book from a humane and beautiful butchery in New South Wales, and long email from a second-generation winegrower in Tasmania who is trying to spread regenerative practices with growers in her region; a raw and unfiltered visit with a group of incredible women of color in wine; and countless emails and texts from Costa Rica, Ecuador, Chile, Vermont, Texas, Arizona, New York, Colorado, New Jersey, Virginia; and here, in my home state, the calls from my people who know when I’ve gone to ground, the walks with my mother, and my little family telling me that no matter how few there are, these grapes taste better than any grapes in the world. The lives behind the words, their own paths, their pain, their joy, so many harmonic notes. We are finding each other and raising an army of will and walk that is poised to give and give more without judgement and with grace. This is only the beginning of the work, and I love beginnings. And now, again, I feel nothing but gratitude for this gorgeous, terrifying adventure I’m on.

THESE ARE JUST A FEW PEOPLE IN THIS FIGHT. MEET THEM, FOLLOW THEM, SUPPORT THEM

- Charles Arnoux-Lachaux: Domaine Arnoux-Lachaux, Burgundy

- Mark O’Connell: Domaine Clos de la Chapelle, Burgundy

- Stephen and Jeany Cronk, Clement Prelat: Domaine Mirabeau, Provence

- Jesper Saxgren: Ecologist, Denmark

- François Chidaine: Domaine François Chidaine, Loire

- Laura Dalrymple and Grant Hilliard: Feather and Bone, NSW

- Abby Rose: Vidacycle, UK and Chile

- Cynthea Semmens: Marion’s Vineyard and Beautiful Isle Wines, Tasmania

- Ricky Taylor and Katie Jablonski: Alta Marfa, Texas

- Christopher Renfro: 280 Project, California

- Sarah Red-Laird: BeeGirl, Oregon

- Robin Touchet and Kevin Pike: Branchwater Farms, New York

- Ashley Rood: Oregon Climate and Agriculture Network, Oregon

- Nicole Maness: Willamette Partnership, Oregon

- Cory Carman: Carman Ranch, Oregon

- Laura Brennan Bissell: Inconnu, California

- Chevonne Ball: Dirty Radish, Oregon

- Roxy Eve Navaraez, Etinosa Emokpae, Imane Hanine, and Jirka Jireh: stratosphere

…and so many, many more.

CLICK/TAP IMAGE FOR GALLERY

I said I had questions, not answers. If these questions are interesting to you then please help me ask them at every level of our interconnected, interdependent lives. LET’S DO THIS TOGETHER.

And for more, see our next series, outcasts.