Dear Friends,

First, a heartfelt thank you, albeit a collective one, to all of you who sent me an email of support after the Revino newsletter. I wish I could respond to every single email, because your words are personal, and they mean a lot to me.

This feeling – of appreciation for your attention, this desire to express my gratitude for the time you take to read these words, for your support of the wines- is the inspiration for the theme of this letter, this long-in-coming announcement of something new! It is indeed wonderful to be able to announce to you that the 2023 Hope Well Pinot, 2023 Hope Well Strings, and the 2024 Chenin Blanc are in the shop and ready to ship! These wines are special to me because they carry the story of our ongoing adventure, of landing and finding our way, and I am so excited for you to meet them. But, you know me, and I know you. We’re not just here for the vintage description and tech sheets, are we? (But do read them!)

No, we’re here because we like more. We are the National Geographic explorers of wine. We want the character backgrounds, the world history, the soundtrack; we want the never-ending story outtake, the Magic Schoolbus version of these bottled tales.

So buckle up, squirrels. We’re headed to the woods.

It is only recently that we have discovered not one, but two domestication points for Vitis vinifera, our beloved European wine grape. It seems grapevines wound tendrils round the hearts and minds of humans in both the Caucasus region and western Asia around 11,000 years ago, and our fates have been entwined ever since.

A native grape climbs with the Spanish moss on a majestic oak in the Carolinas

Like wings, eyes, and venom, vining is an example of convergent evolution, or the independent emergence of specific traits in organisms that do not share a common ancestor. In other words, vines did not happen one time, but rather appear to be an adaptation to evolutionary pressures that make vining advantageous. Vines appear to have once been trees that took a gamble on a different growth habit to get better access to what they need.

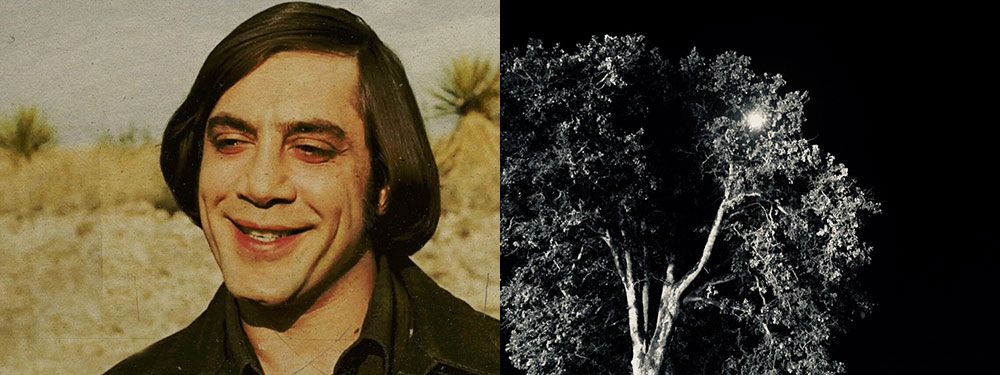

So while human and grape may dominate the plot of the story of wine, it should not be surprising that the focus character today set the mold for the supporting role that carries the whole movie. This is the story of wine’s DeNiro as Vito Corleone in the Godfather II, of wine’s Heath Ledger as the Joker, of wine’s Harrison Ford as Han Solo. Friends, I submit that in the story of wine, the backbone holding the plot in the air is none other than the mighty oak, genus Quercus.

Be honest, would the franchise have made it without Han?

For wine, the oak is irreplaceable. While we do not know what trees the first Vitis climbed, it is certain that by the time grapes were coveted by humans, they grew amongst the oaks. In the northern hemisphere, Quercus, the oak genus, has the most species and is native to nearly every biome in which grapes are grown, and they are certainly native and ancient in the Caucasus and western Asia, whence human hands peeled Vitis vine from native forests and bent them to domestic will.

Oak wood is strong and hard, and built many early wineries as well as the casks to age in. Their slow-growing nature produces small, tight grain that allows for very slow, controlled aging with oxygen. Oaks produce a unique array of phenolic compounds and sugars that impart flavor and aroma that have become almost inseparable from wines that age. These are obvious contributions, but there are more.

If terroir must always include climate, geology, topography, and the human component, one could argue that the oak should stand as tall as any influence. If you scoff, I will let it slide because you probably don’t read Applied and Environmental Microbiology or swim around in the vast volumes of academic literature devoted to microorganisms. We are only beginning to fully appreciate the role of oaks as hosts to the Sine qua non of wine, yeast. Specifically, the largest reservoirs of indigenous strains of Saccharomyces yeast in nature are found in the bark crevasses, leaf surfaces, and exudates (tree goo) of oak trees. In fact, it has been shown that gene flow between oak habitat and nearby vineyards allows for the generation of populations that become endemic to a winery that does not inoculate with commercial yeasts. Pull that little nugget out at your next dinner party.

Oaks standing watch over Hope Well

So, oak is a dominant figure in the oak story. Oak is Javier Bardem’s Anton Chigurh in wine’s No Country for Old Men. Would you even bother without him? But friends, wine is a laughably miniscule part of the oak’s story.

In ecology, any organism whose influence outweighs its relative biomass is considered a keystone species. These are the ecosystem scaffolding, the definers, without which the ecosystem as it exists would not be possible.

Anton and the brooding oak. You see it, right?

Oak. Acorns germinate soon after they fall and before the first frost, they send a taproot deep into even the most shallow, poor soil, and that is all they do before the winter comes. In their first year, oaks will produce only one set of true leaves, remaining a few mere inches above ground, though below ground they are anything but small. All the energy from those first few leaves is poured into building a foundation, ten times the biomass below ground, a silent statement of their commitment to time and place. At any given age, the body below will be three times the width of the canopy, anchoring fragile hillsides, expanding the capacity of the watershed exponentially, filling the heavens with upwards of 700,000 solar panels alchemizing starshine to feed legions. And while she may pass 4 decades before a single acorn falls from her branches, over the course of her very long life she will birth several million acorns.

The oak is as ancient as her relationships. The flashy jays so common here share a common ancestor from Asia, where oaks evolved, and their very body plan is built around their relationship to the oak. Their beaks are designed to rip open a tough husk, and they have an expanded esophagus to accommodate many acorns, a big, nutritious seed capable of sustaining a large bird capable of covering great distances. They don’t cache their food, instead burying single acorns throughout their territory — up to 4500 in a single autumn. The limitations of their memories result in a net additional 3000 potential oak seedlings per bird, per year across their 7-17 year lifespan.

The Steller’s Jay, Cyanocitta stelleri

Acorns are the wildlife MRE (Meal Ready to Eat, a survival brick of intestinal torture known to any armed service member or wildland firefighter), providing enough protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals to sustain generations of woodpeckers, squirrels, deer, bears, mice, voles, turkeys, quail, ducks, and so many, many more. The acorn is itself an edible home for tiny weevils, you may have seen their little exit holes if you collect acorns. These weevils belong to the largest family of animals in the world and while you may never actually see one, their larvae are one of the most abundant sources of protein for animals up the food chain in our neighborhood. Their excavated acorns make perfect homes for temnothorax ants, which are one of many sources of insect food that drive the terrestrial food chain.

Plants make insects, and oaks make considerably more insects than we appreciate. Most of our songbirds are insectivores, and to survive the winter they depend on abundant insect populations. To be clear, not all plants support the same insect productivity. Oaks host two to five hundred species of Lepidoptera, the moths and butterflies alone, including The California Sister, Adelpha californica, Propertius Duskywing, Erynnis peropertius, Mournful Duskywing, Erynnis tristis, and Golden Hairstreak, Habrodais grunus. Gold-hunter’s Hairstreak butterflies, Satyrium auretorum, are known to use Oregon white oak as a larval host plant; these butterflies use the oak to complete their early and most vulnerable stages of their life cycle, while adults may use the oak for shelter and perching while looking for mates.

You’ve no doubt observed the marcescent leaves of the oak, holding on considerably longer than virtually all other deciduous trees. While not fully understood, this adaptation, along with the waxy cuticle that helps impart drought persistence, make oak leaves an invaluable currency for our food web. In any given temperate ecosystem, 75% of insect food for birds and animals is produced by only a few plant genera. Here, unquestionably, oak reigns again.

Collembola on mossy bark

While in agriculture we tend to focus a lot on generalists, some of our greatest insect allies are specialists, relying on but a few plant hosts to complete their life cycle. Lift a single layer off the oak leaf litter and you will barely scratch the surface of the collembola, bristletails, carabid beetles, rove beetles, nematodes, worms, sow bugs, pill bugs, mites, and more. These detritovores perform the task of breaking down leaves, and are the base layer of the world-wide animal food pyramid, their bodies feeding everyone from spider to snake to nuthatch.

The marbled green, Cryphia muralis, belongs to the family Noctuidae, one of many moth families specifically adapted to blend into the lichen speckled bark of oak trees.

In living and dying these oak dependent animals are also pivotal to the turning of our nutrient cycle. Critical micronutrients are locked in deep soil columns, in trace amounts. The deep, deep roots of the oak access these minerals and when the leaves fall those minerals replenish our topsoil for growing nutrient dense crops. The blankets of oak leaves that cover the ground break down at three times the rate of alder, maple, or ash. Their waxy cuticle provides a brilliant structure to the ground cover, preventing erosion and evaporation, cooling the soil and holding water in times of drought.

Slime mold growing on a marescent oak leaf

This leaf litter may be the greatest unseen wealth of our oak-strewn lands, for it feeds the armies of untold soil dwelling insects and microorganisms that feed our cash crops and keep our soils productive. The secondary plant compounds, the tannins and phenolics are that are in each of the 700,000 leaves a mature oak drops every year are at once defensive against invading pests and medicine for a healthy food web. All organic matter is not created equal, you see. We need fast and slow food for the whole web to thrive and grow throughout the year, and oak litter can feed soil for up to three years, building deep banks of residue for fueling crops and nursing future oak seedlings.

The next generation

The word persist comes from the Latin sistere, to stand, and per, meaning through, steadfastly. It is a standing verb, not a moving one. To persist is oak as verb. The oak is a standing universe of connections, and is a touchstone of this land, its history and people. In founding the Oak Accord in Oregon, we saw the oak as a catalyst for dissolving the perceived mutual exclusivity between agricultural productivity and the healthy habitat on which it depends.

What I have tried to convey with my illustrated fraction of our food web is that the oak is both a keystone to and a metaphor for agriculture. The lives and livelihoods of this state and country depend on the quality and abundance of our agriculture, but our farmers are becoming few and aged, and have been largely ignored since the call of the great war. The genus Quercus, the oaks, support more life forms and interactions than any other tree genus in North America, but we see them less and less. As we displaced indigenous burning which regenerated oak habitat with mowing and cultivation, the recruitment of young oaks has ceased, lost to the blade and crop. The next time you enjoy the shade of a crowning oak in the parklike surrounds of some lovely tasting room, have a look around — where are the next generation?

This is my Earth Month love letter. We had a mast year here in Oregon in 2023. My daughter Stella and I have decided to offer to flag tiny seedlings where they’ve sprouted to local landowners so that they can be protected from mowing and preserved for the next generation of centenarians. They are EVERYWHERE right now. Next time you walk in a field, keep your eyes on the ground and some tape in your pocket. The future forest is underfoot. Her roots are ready and adapted to where she was born. Her chances of surviving in this moment, in this climate, are manifold, without any water or help from us, many times greater than any tree we would plant from a container. They just need a chance.

This is the year and decade of oak. Plug in if you can. There are so many ways to act positively where we live. And it feels so damn good. Treat yourself to that feeling.

~ Mimi

The Acorn and the Oak

Within the damp and clinging earth,

Where darkness spans a world unseen,

An acorn dreamed; and, dreaming, saw

Blue skies and forests green.

—

The Acorn and the Oak

By Ella Maxwell Haddox